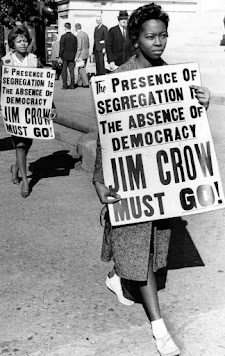

In 1964 and 1965, America witnessed two of the most transformative legislative achievements in its history. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 delivered immediate, concrete changes to millions of Americans who had endured decades of systematic discrimination and exclusion from full citizenship.

The moment President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964, the fabric of American society began its radical transformation. Within hours, African Americans courageously tested these new protections by walking through the doors of previously segregated establishments. In cities across the South—Atlanta, Birmingham, Memphis—black families sat down to meals at restaurants that had violently rejected their presence just days earlier. Hotels that had systematically turned away black travelers now found themselves legally required to provide equal service. The simple dignity of ordering coffee at a lunch counter, an act that had triggered brutal confrontations during the sit-in movement, suddenly became a federally protected right.

Corporate America responded with unprecedented speed to the employment provisions of Title VII. Major corporations, recognizing that federal contracts worth billions hung in the balance, moved swiftly to integrate their workforces. Companies like Lockheed, General Motors, and IBM dispatched recruiters to historically black colleges and universities for the first time in their corporate histories. Black professionals discovered opportunities in engineering, finance, management, and technical fields that had been hermetically sealed against them. Women experienced equally dramatic breakthroughs as the inclusion of “sex” in the legislation meant employers could no longer post job advertisements specifying “men only” or maintain the discriminatory pay scales that had defined the American workplace.

The Voting Rights Act unleashed an even more profound transformation. Federal registrars descended upon counties with documented histories of voter suppression, accompanied by Justice Department officials who monitored every step of the registration process. In Selma, Alabama, where peaceful voting rights demonstrators had been brutally beaten on the Edmund Pettus Bridge just months earlier, black voter registration skyrocketed from a mere 2% to over 60% within the first year. Throughout Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana, hundreds of thousands of African Americans registered to vote in 1965 and 1966, many experiencing the fundamental act of citizenship for the first time in their lives.

The psychological revolution proved as significant as the legal one. Black veterans who had fought fascism overseas could finally exercise democratic rights at home. Elderly citizens who had paid taxes faithfully for decades could at last choose their representatives. Parents could look their children in the eye and declare them full American citizens, not second-class inhabitants of their own country. The climate of fear and intimidation that had suppressed entire communities began dissolving as federal protection became tangible reality rather than distant promise.

These landmark acts catalyzed unprecedented coalition-building among America’s diverse communities fighting discrimination. The Civil Rights Act’s comprehensive language protecting religion and national origin extended new safeguards to Jewish Americans, Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans, and other minorities who had faced their own forms of systematic exclusion. Organizations representing different ethnic and religious communities recognized their shared stake in defending and expanding these protections, creating powerful alliances that would reshape American politics.

Even resistant Southern states found themselves adapting with surprising rapidity. Business leaders discovered that segregation had become not merely morally indefensible but economically suicidal. Cities competing for new industries, federal installations, and investment capital had to demonstrate measurable progress toward integration. Municipal officials who had built careers on racial demagoguery quietly began implementing compliance measures, recognizing that the old order had collapsed.

The velocity of transformation astonished observers across the political spectrum. In 1963, Alabama Governor George Wallace had theatrically blocked university integration, proclaiming “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” By late 1965, black and white students attended classes side by side in Alabama’s state universities. Lunch counters that had been literal battlegrounds became spaces of peaceful integration. Polling places that had been fortified against black participation became symbols of democracy finally fulfilling its promise.

These victories transcended symbolic achievement—they represented concrete improvements in millions of individual lives. A father in rural Mississippi registering to vote for the first time at age fifty. A mother in Birmingham applying for a supervisory position previously reserved for white employees. A family in Atlanta enjoying dinner at an upscale restaurant that had excluded them the previous month. A brilliant young student enrolling in a prestigious university that had barred people of her race since its founding.

The Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act proved that federal legislation could indeed transform entrenched social structures and that America possessed the capacity to honor its founding principles. These weren’t merely paper promises or legislative theater—they were authentic revolutions delivered through democratic processes, demonstrating that the arc of justice could bend decisively toward equality when backed by moral courage and political will.